originally published 4.7.2017

Essay: The Once, Present, and Future King: Are Refn’s ‘One-Eye,’ ‘the Driver,’ & ‘Lieutenant Chang’ the Same Character?

originally published 7.14.2017

Like David Lynch, there is a thematic tipping point in the filmography of Nicolas Winding Refn, a movie in which the director discovered an overarching concept that he would explore from alternative angles over the course of several films. For Lynch, that point was the original Twin Peaks series, and the concept was one of duality, specifically duality of consciousness within the same persona, which he has since explored in Fire Walk With Me, Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire, and presently in the third season of Twin Peaks. For Refn, this point is the 2009 film Valhalla Rising, and the concept is one of transformation. All three of his films that follow Valhalla Rising – Drive, Only God Forgives, and The Neon Demon – deal with central characters in the process of changing themselves, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse, regardless with mixed results. But speaking of Valhalla Rising, Drive, and Only God Forgives (all made within a four-year period), there’s another, more confounding and intriguing connection, according to Refn himself: “One-Eye,” “the Driver,” and “Lieutenant Chang” are iterations of the same character, not the same type of character, but the same actual character, one the director describes as “a mythological creature that has a mysterious past but cannot relate to reality because he’s too heightened, and he’s pure fetish.”1 Further elaborating, Refn says, “One-Eye, Driver and this guy, the Unnameable [Chang] … are very much rooted in fairy-tale mythology, of people with supernatural powers. Again, part of my, I guess, intense fetish of masculinity.”2

This definition positions these men as destined for more than mere manhood, it establishes them as men who are isolated from the world and indeed reality because of their shared destiny, which is a kind of long-gestating chrysalis transforming them into the heroes they are meant to be. For One-Eye, silent figure at the center of Valhalla Rising, the supernatural power Refn refers to is precognition, or the ability to see the future; for the Driver, eponymous protagonist of Drive, it is invulnerability or superhuman resilience; and for Lieutenant Chang, the “God” of whom the title Only God Forgives refers, it is a power so complete and fully-realized that it borders upon omnipotence. In each film, these superpowers are used not for the betterment of he who wields them, rather for protecting or avenging innocents. One-Eye sacrifices himself for The Boy; the Driver crashes his life to help Irene and her son; and Chang acts as judge, jury, and when needed as executioner in his sphere of existence, ensuring the wicked keep away from the innocent, or failing that, using them as an example for others who would be tempted to emulate their behavior. By exploring these men as individuals, how they relate and how they differ, we reveal how they fit together into a greater mythological narrative of heroism, defeat, redemption, and the meaning, worth, and consequences of superiority.

To begin with, there are several surface similarities shared by these characters, namely that all are either mute or speak as little as possible, all have mysterious and unexplored pasts, almost like they weren’t born of women but rather conjured into existence by some greater power, all move through life trying (but failing) to avoid emotional attachment, which they perceive as worse than a weakness, instead a fatal flaw, and – most importantly – all are fetishistic manifestations of masculinity, meaning they’re powerful, violent, physical over verbal, and caught between states of being that are both civilized and primal. At the same time, though, these men are also noble, protective, loyal, disciplined, and selfless. They are heroes. Unconventional ones, to be sure, but so too are their worlds unconventional. We get the heroes and villains we deserve, never any more, never any less.

Despite these similarities, though, each man represents a distinct phase of their communal evolution, One-Eye the discovery or becoming phase, the Driver the mastery phase, and Chang the fulfillment phase. Their hero’s journey is one of death and rebirth, shedding skin as one becomes the other, each time emerging into a world that has changed but not to pace with them, leaving them forever outside the realm of humanity, lonely gods who protect at their own peril.

One-Eye begins his journey – their journey – as a lowly thrall, or slave, owned by a Norwegian chieftain who uses the man’s physical prowess, itself qualifying as superhuman, to fight other thralls to the death for sport. One-Eye at film’s start is less than a man, he is a wild animal never let off his leash, he is a tool of man, a domesticated beast. As he progresses through his phase of the larger journey, aided by his precognitions, One-Eye acquires his freedom, survives overwhelming adversity at every turn, discovers his humanity, and ultimately dies a hero, sacrificing himself for the sake of The Boy, who helped to spur his transformative exodus. One-Eye’s death, though, is as mentioned more of a rebirth, it is his spirit shedding what it was born as in favor of what it and he will become in his next incarnation, namely a more-formed hero, one already aware of himself. This is essentially how I believe Refn connects the characters in a narrative of logic (if even he does), as reincarnations of the same soul. Speaking somewhat to this idea, Refn says of One-Eye, “He’s essentially a god, but a god in sense of what the others make of him. He has powers, but doesn’t know why he can see the future. He doesn’t realize why, until he participates in a hallucinogenic journey, in which he becomes active.” 3

“A god in sense of what the others make of him” would seem to tell us that the character isn’t immortal as he is spiritually singular, a being of power in a powerless world. He is superior, but in a way that is to be feared, not celebrated, and feared power is almost always worshipped in the history of man, it is something we deify to avoid being crushed by it. Not all gods want to be worshipped, though, and One-Eye’s horrific background, what we see of it, at least, has left him understandably distrustful of all men. But this is how he “becomes active,” by setting aside his distrust, by recognizing his uniquity and using it to save another, The Boy, thus transforming himself, through death, into a willing hero. A hero named The Driver.

“He’s the man we all aspire to be, but he wasn’t meant to live in the real world, he’s too noble, too innocent. In the old days, a knight would put a sword between themselves and a woman. And in Los Angeles, a man like this exists.”4 This is one of the ways Refn describes the Driver, and it is a fitting image for this phase of the character’s evolution. The Driver is a hero at his film’s outset, he is aware of his particular abilities and uses them to work as a stuntman and getaway driver, both of which are inherently dangerous professions. He is a reluctant hero to be sure, guarded and cautious, but reluctance is a chivalrous quality, the best knights are never boisterous, they are respectful of the power they wield and unleash it only to protect or defend.

The Driver might not be able to see the future like One-Eye could, but that’s because he’s better prepared to handle the present. If Valhalla Rising is about discovery, Drive is about mastery, it is the sequel to the origin story in which our hero, now aware, or as Refn described it, “active,” becomes one with his powers and his persona, he accepts himself and starts towards becoming his best version, which is the destiny of every hero. Irene is the impetus of this. The allure of her innocence and its ability to break through the Driver’s self-imposed isolation and engage him emotionally, like The Boy did One-Eye, starts him becoming better, yet again through sacrifice. The Driver agrees to help Standard rob the pawn shop not for the man’s sake but for the man’s family’s, Irene and her son. And when the robbery goes horribly wrong, resulting in Standard’s death and the Driver wanted by the mob for stealing their money, instead of speeding off into the sunset like most criminals would, instead of saving himself, he sticks around to finish things, knowing if he goes then the next name on his enemies’ list is Irene’s. Once again through a fetishistic frenzy of violence the Driver forces another evolution of his character, one in which his spirit masters its being and the two halves – man and mythical hero – forge into one. The Driver solves his problem, he saves Irene, and he survives. For how long is left intentionally vague, but the last we see him he is alive, and he is changed from the man we first encountered, he is now able to allow himself connection, he has proven to himself he can keep safe the ones he loves. Thus, when he is reincarnated next, as Lieutenant Chang, he is a vengeful shepherd to a flock of citizenry, a silent but present god who can forgive, though not without penance.

Chang is the most static of the character phases, he remains the same figure from start to finish because he is actualized, he is the fulfilled potential his spirit has been pursuing through its incarnations. This makes him, to those who live in his shadow, a kind of god “in the sense that God in the Old Testament is saying ‘I can be cruel, you have to fear me’ as ‘I can be kind, you have to love me.’”5 He is the hero his wards deserve, one who is brutal but fair, and one who views the world as simply as he governs it. As Refn says, “Chang’s way of life is ‘you are the consequences of your actions and nothing ever goes unpunished.’”5 This is what his spirit has learned across the lifetimes, that it isn’t who you are that matters as much as it is what you do with who you are. Life is a series of consequences, and the only difference, at the end of the day, between heroes and villains is intention, will. This spirit has chosen, at times against its stronger notions, to be a hero, to give of himself for others, to protect, but in a world like the one portrayed in Only God Forgives (and Valhalla Rising and Drive), being a hero requires mercilessness, it means destroying evil, be that evil the heart of a man or just his hands, and it also means living with the ramifications of said mercilessness. In the other two films, these ramifications are an end to or abrupt shift in life; in Only God Forgives, they are the preservation of life as-is and security against those who would threaten this.

Therefore, if One-Eye is escaping and overcoming his past, and the Driver is confronting and accepting his present, then Chang is shaping the future, he is creating order by action, he is imposing a moral system of which he is the central figure, he is, in essence, creating or at least allowing created a religion around himself. He is his superpower now, everything he does, every move he makes, every action he takes, it is all perfect, effortless, and effective. Emotionally, too, he is his most-evolved. There is love in Chang’s life, or at least a wife, and there is passion, as his affinity for karaoke demonstrates. He is no longer a soul in isolation, he is a known figure, one who proudly walks the streets and commands respect everywhere he goes. These are normal pleasures the Driver wouldn’t allow himself and One-Eye couldn’t conceive of, they are the result of a perfect harmony of spirit and being, a singular, evolved persona who has found the balance for which he’s spent millennia searching. Which is why Chang is also the only incarnation of the character who not only survives unquestionably, he is never even injured. Chang is untouchable, something he has earned from the brutality One-Eye endured then the Driver wrestled under control.

Looking then at the overall evolution, our hero begins as a beast, a product not of his own will but the actions of others, a thing made, not born. Through an injection of innocence into his life, The Boy, and the aid of his own precognitive powers, he escapes captivity and learns to walk upright, as it were, in the process becoming a self-sacrificing hero. Next born he is a being comfortable if cautious with his exceptionalism, he knows that he is a weapon, capable of being used for good or evil, and struggles to stay on the right side of that line. Having experienced and benefitted from a connection in his previous incarnation, he is more susceptible to the world of man and those who inhabit it, and his interactions with Irene, like any exercise, strengthen his emotional muscles, in turn preparing him for the feat to come: mastering his powers to protect the innocent, learning to control the beast who still lurks inside and turn all his rage into a force for good. He does this. He controls himself, wields himself responsibly, and though injured, perhaps mortally, he spares innocence further pain and is rewarded himself with the final phase of his evolution: omnipotence. Here, at the pinnacle of his potential, he is no longer a leaf in the winds of the world, he is the wind, he is the action and the reaction, the end-all be-all, the Alpha and the Omega of morality, of justice, a son of no one who becomes a father to all.

Looking then at the overall evolution, our hero begins as a beast, a product not of his own will but the actions of others, a thing made, not born. Through an injection of innocence into his life, The Boy, and the aid of his own precognitive powers, he escapes captivity and learns to walk upright, as it were, in the process becoming a self-sacrificing hero. Next born he is a being comfortable if cautious with his exceptionalism, he knows that he is a weapon, capable of being used for good or evil, and struggles to stay on the right side of that line. Having experienced and benefitted from a connection in his previous incarnation, he is more susceptible to the world of man and those who inhabit it, and his interactions with Irene, like any exercise, strengthen his emotional muscles, in turn preparing him for the feat to come: mastering his powers to protect the innocent, learning to control the beast who still lurks inside and turn all his rage into a force for good. He does this. He controls himself, wields himself responsibly, and though injured, perhaps mortally, he spares innocence further pain and is rewarded himself with the final phase of his evolution: omnipotence. Here, at the pinnacle of his potential, he is no longer a leaf in the winds of the world, he is the wind, he is the action and the reaction, the end-all be-all, the Alpha and the Omega of morality, of justice, a son of no one who becomes a father to all.

Regardless of whether or not Refn returns to the character, knowing One-Eye, the Driver, and Lieutenant Chang are tied to one other tells an even larger, more fascinating story than their individual films, a story that takes a thousand years to unfold, a spiritual epic akin to that of Jesus, of Mohammad, of the Buddha, but tied to the ways of the world unlike any of those, a narrative of birth through cruelty, ascension through violence, and redemption through death.

Amen.

**author’s note: this was written before the announcement and release of Refn’s THE NEON DEMON and his collaboration with writer Ed Brubaker, the series TOO OLD TO DIE YOUNG, which are, in my opinion, undoubtedly the fourth and fifth chapters in the One-Eye mythology. Analysis forthcoming.**

Flawless Frames: NIGHTCRAWLER

Cinematographer Robert Elswit won the Oscar in his field for Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film THERE WILL BE BLOOD. Seven years later, with acclaimed writer Dan Gilroy’s directorial debut NIGHTCRAWLER, the DP created a visual aesthetic that in many ways can be considered a dark reflection of the former film.

In both, the landscapes – rural and urban, respectively – are central to the narrative to the point of being silent narrators that forge and in many ways control the particular characters that roam them.

In both, it is the lone figures against these landscapes that exemplify the narrative conflicts, internal and external.

But where THERE WILL BE BLOOD is blinding with uninterrupted sun and fires that pierce the nights, NIGHTCRAWLER is built of shadows, the shapes that move among them, and the glints that illuminate not the foreground but the deepest, darkest, most dangerous corners. This frame in particular, with the addition of smoke to shadows and Lou Bloom holding the old, diffuse like, perfectly captures these notions.

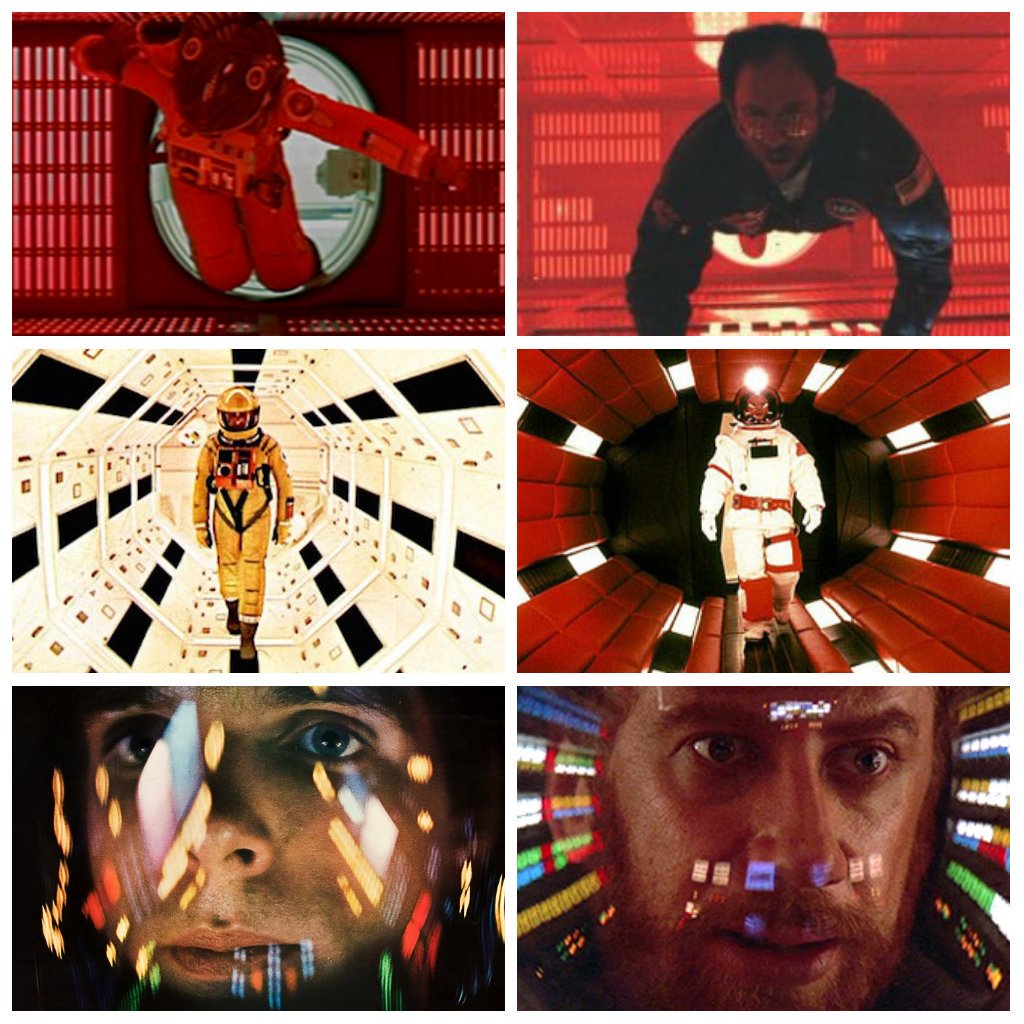

CinemaGrids: 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY/2010 THE YEAR WE MAKE CONTACT

It’s tough to follow Stanley Kubrick, and it’s even tougher to follow his masterpiece – the groundbreaking, genre-shifting, immortal 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY. But Peter Hyams did just that with 2010: THE YEAR WE MAKE CONTACT, based on Arthur C. Clarke’s literary sequel to the original source material. Hyams realized, wisely, that the trick here wasn’t to break so much new ground as much as it was to continue the aesthetics and atmosphere of Kubrick’s triumph. To that end, there are several visual nods to the first film in the second, the most masterful of which are collected here, next to their inspirations.

Essay: “The Lord Can’t Hear You, Daniel” – The Impact of Silence on THERE WILL BE BLOOD

originally published 11.5.2016

Film is both a visual and a narrative medium and as such, the entire point of it is to tell by showing. Where literature has the power to grant us access to a character’s thoughts, film allows us to experience their emotions via expressions, body language, and subconscious communications to which words could never do justice. And even though the addition of sound to movies revolutionized the medium and how effectively it could tell its stories, there are still moments that are better told by images alone, with a score perhaps but no interfering dialogue, just the subject, the scene, and narrative silence.

Think of David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence and [SPOILER] its ending that features a silent family dinner that emotionally balances the explosive and excessive violence that precedes it. Or Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, a film about sound that scores its most pivotal scene in silence as Harry Caul destroys his apartment searching for the listening device his paranoia has convinced him is there. Or the staggering 26-minute heist scene from Jules Dassin’s Rififi ‐ widely regarded as the best heist film and perhaps the greatest French noir of all-time ‐ that takes advantage of the tension silence creates to craft a thrilling cinematic experience. And of course, who could forget the greatest and most purposeful dialogue-free sequence in cinema history, the “Dawn of Man” sequence that opens Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey? Without a single word Kubrick cinematically birthed all of humanity and civilization.

In the modern-era, hands down the greatest use of narrative silence has to be the 14-minute opening of Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, in which the entire world of the film, the complete character of Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day Lewis), and the atmosphere of the story are established before a single word is spoken. However, the opening scene is just one example of the impact silence has on There Will Be Blood, a film that makes frequent use of dialogue-free scenes throughout its two-and-a-half-hour runtime, to various effects.

But, of course, it all starts with that opening. Let’s call it the “Dawn of Dan,” because like the sequence in Kubrick’s film, Anderson’s silent opening shows an ascent, an evolution of character from one thing to another. In Plainview’s case, we see him as a solo prospector, a lone, desperate figure in the barren wilds of the American desert scavenging below the surface for unpromised riches. We see him hire on a team of men, establish small derricks, suffer small defeats ‐ like the accident that kills one of Daniel’s men and leaves Daniel to care for the man’s orphaned infant son as his own ‐ and earns small successes in the form of black lakes of oil. By the time Plainview does speak, his infamous “I’m an oil man” monologue, we know almost all there is to know about him: we know he in inexhaustible in his quest for wealth and success, we know he is not afraid to get his hands dirty, we know he is not afraid to get his soul dirty, we know there is a certain callousness to his spirit, but at the same time we know he is capable of great warmth, compassion, and tenderness in dealing with H.W., his “son,” and we know that he is a force of will, of persona, and indeed of nature. The only non-ambient sound in these scenes is Jonny Greenwood’s dolefully screeching score, which adds a sense of tension, like this whole world is hanging by razor wire stretched to its limit, ready to snap and slash everything apart. Furthermore, by following all we’ve seen in silence with an eloquent monologue as his aural introduction, Plainview’s capabilities and perceived potential are augmented to the nth degree; he is as smart as he is able and thus now also a force to be reckoned with. Silence in the opening is a narrator, then, it is the method by which we learn about the world we’ve just walked into, it is the injection of emotion that infects us with the film’s intent, the only cure for which is letting the narrative run its course.

Beyond the opening, silence is also used throughout the film to enhance a sense of isolation, be it geographically, socially, or spiritually. Sweeping panoramas of the landscape and static shots of men against the expanse saying nothing, just being among the absence, reveal what a lonely life Daniel, his son, and his team live, how far removed they are from “civilization” or even just the common bustle of everyday living, and make us wonder what kind of man with what kind of temperament from what kind of background would willingly give himself to such a life. Scenes of humble people huddled over meager meals communicating only by the scrape of utensils against empty bowls reveal the dependence that daily life used to entail (and does still though less noticeably) and how so often people put their fates in the hands of a god ‐ itself another silence, a silent acceptance of personal powerlessness ‐ only to run through his fingers. There is no god in this corner of the country, nothing can grow here, nothing can flourish, only rocks, angry and wrestling each other for millennia, squeezing every last, black drop of blood from one another. This is a place of savagery, not salvation, this is a place no faith can take purchase because there are no eternal rewards, only those of the fleeting, earthly variety. This is a place where prayers aren’t answered because they aren’t heard and are therefore better left unsaid, or better left to silence.

Silence also enhances dread in There Will Be Blood. In scenes such as the one where a worker’s bumble leads to the death by falling object of another worker in one of Daniel’s wells, or when Daniel sits watching his derrick burn, or the aftermath of H.W.’s accident, or Daniel chasing H.W. through the night after the boy set fire to their cabin, the lack of dialogue and in some instances score adds the tension of silence to the scene, its own inevitable breaking highlighting the same fragility in narrative; we know a fallout is coming, an emotional snap that will merge the physical chaos of what we’re seeing with the emotional chaos of what the characters are experiencing, but we don’t know when that moment will arrive, we can’t, because there are no aural clues or cues in the scene, nothing to mark our place in the emotional progress of the characters. Silence here is a misdirection, or rather a manipulation of expectation, leaving us in the dark as well.

In addition to mirroring his isolation, silence also reflects Daniel’s superiority, at least from his own perspective. There Will Be Blood is riddled with scenes of Plainview off on his own staring in silent contemplation at his land, his camps, his derricks, his son ‐ his empire, in short, his dominion. In this silence his realm becomes the only thing in existence and he the god’s-eye view of his own life. Daniel is a man who seeks no council, we never see him even entertain the notion of a lover, let alone a spouse, and his only partner is his adopted son, who he can bend and shape to his will until he cannot, and then he can dispose of him by stashing him off with a tutor in a school for the deaf and mute. The Plainview universe is of Plainview’s own making, his will is the big bang and his vengeance controls it. Thus in scenes when he surveys what he has made there is no dialogue, because there is no voice more important than his, and he does not need to hear it aloud.

And finally, silence in There Will Be Blood is used to illustrate emotional intimacy and distance, the latter here being different from emotional isolation, because it isn’t drawing attention to a character’s loneliness, but rather a character’s specific rejection of another person, a willful withdrawal of attachment. I am speaking, of course, about Daniel’s relationship with his son. Before the accident which robs the boy of his hearing, the silences between the two of them were of the comfortable variety, the sort that occurs not because people have nothing to say to one another, but because they know each other so well and are so synchronized in thought, belief, and rationale, that theirs is a language involving unspoken facets. But after the accident a different kind of silence descends between them, a silence meant to be a solid thing blocking one from another. There’s nothing Daniel can say to take away his son’s infirmity and set their dual destinies back on track, so he will say nothing more, he will let his prolonged silence, here willful ignorance, erect a wall between he and his son that neither will ever get over, around or under. This is the great silence of There Will Be Blood, the one that pervades, that exists eternally, and that will cast a shadow over both men all their days.

Even the last, tumultuous scene of the film utilizes the power of silence, which initially might strike you as odd given that it’s a long, dialogue-driven scene, a kind of opposing force to the silent opening. But consider this: the entire movie to now we have watched Daniel make himself. We haven’t heard it, we have watched it, that’s what those first scenes were showing, how the man became himself. But when it comes time for Daniel’s final devolution, when it comes time for the tension to snap and the whole of him to collapse into his liquor-fueled madness, it isn’t shown as much as it is told, he talks himself into the frenzy that crescendos in the murder of Eli. The silence of the opening and the rest of the film is refuted, it is dominated, and as a result we feel the impact of its absence. We juxtapose the unfettered chaos of the ending against the restrained unravelling of the film until then, and for our efforts we are rewarded with the gut punch of the film’s final moments.

When Daniel is being baptized by Eli, the preacher asks him if he is a sinner. Daniel says he is, but in a low, calm, barely-audible voice to which Eli replies:

“Oh, the Lord can’t hear you, Daniel. Say it to him. Go ahead and speak to him. It’s all right.”

Eli here recognizes silence is Daniel’s chief defense, it is his refuge, his council, and his power; as long as he is kept by himself no other man can own him. But Eli wants Daniel owned, he wants to be the agent of Daniel’s ownership because he believes that will make Daniel beholden to him and he wants to bend the man’s power to his own benefit. But as he learns in this scene and with more finality at the end, the only think worse than a silent Plainview is a screaming one, and not even the Lord is refuge from a man muted to reason by ambition.

Flawless Frames: THE ASSASSINATION OF JESSE JAMES BY THE COWARD ROBERT FORD

I’m starting this column with my favorite frame from my favorite cinematographer: Roger Deakins.

This frame, from Andrew Dominik’s 2007 film, is emblematic of Deakin’s aesthetic – simple, elegant, resonant, and more powerful than any bit of dialogue, no matter how brilliant, could ever hope to be – and the very definition of “flawless.”

Deakins shot THE ASSASSINATION… the same year he shot the Coen Brothers’ NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN. He was Oscar nominated for both films, but lost to Robert Elswitt, DP of THERE WILL BE BLOOD.

Essay: The Sang-Froid of DRIVE

originally published 11/29/2016

Films often change their titles when they are translated into other languages. Usually it’s a matter of comprehension: a phrase or word in English might not have a comparative in another language, or perhaps the new culture requires a different explanation or encapsulation of what the film is about. In China, this year’s Ghostbusters is called Super Power Dare Die Team; in Denmark Die Hard With A Vengeance is the decidedly-adult sounding Die Hard: Mega Hard; and in Italy Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind translates to the much blunter If You Leave Me I Delete You. One culture might make the film, but each culture that views it adds a layer of meaning and interpretation by what they title it, in many cases establishing different emotional and tonal expectations from their American counterparts.

As I discovered recently when replacing my personal copy, the French title of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive is one such of these instances. The title there is Sang-Froid (sang-frwä), a noun which is defined by Webster as “composure … sometimes excessive, as shown in danger or under trying circumstances.” Basically it’s grace under fire but turned up a notch in terms of the grace taking on a more masculine connotation as coolness and the fire becoming a full-blown inferno. There is no equivalent term in English but as that definition could pass perfectly for a one-line description of The Driver (Ryan Gosling), in several ways it’s a more fitting title than even Drive.

Besides being a noun instead of a verb, thus placing the emphasis on the character of The Driver himself rather than his actions, Sang-Froid conjures different connotations than Drive, which ostensibly establishes the film as one based on action; Sang-Froid implies a more introspective film and would seem to suggest that whatever thrills are coming aren’t derived from the events or occurrences The Driver inflicts or survives, but rather from the motivations within himself that puts him in their path to begin with. And when the events and occurrences turn excessive, so too does The Driver’s sang-froid, ultimately leading to his undoing.

In terms of how The Driver encapsulates the meaning behind “sang-froid,” honestly, how doesn’t he? As I said, the term is pretty much a perfect description of him, and nearly everything he does reiterates this. It’s practically patterned behavior: in his professional, personal, and romantic relationships he projects constant composure, a façade which has the side-effect of blocking him from objectively living his life. He becomes a slave to his composure, in a sense, it is the thing to be maintained above all else, his own personal status quo, and in certain instances this composure becomes excessive to the point it drives people away, turns friends to enemies, or manifests in irrevocable violence.

In the opening scene while waiting to pick up his passengers The Driver is quiet, calm, his jaw locked and his toothpick steady, even later as he weaves in and out of traffic at 80 miles an hour; but he gets a little too cool, following a police car when he should be playing it safe and avoiding them. This decision puts The Driver and his clients on a path that leads them into the sights of the police helicopter, and though he eventually shakes the cops and makes a clean getaway, his excessive exhibition of composure had the immediate consequence of increasing the peril of his situation, something with which it was already overwrought. For The Driver, however, the accomplishment isn’t the getaway, it’s the elusion, it isn’t about delivering his clients, it’s about tempting fate and taunting authority; and, of course, it’s about testing his composure against trying circumstances, it’s about tempering it, making it stronger.

In his relationship with Irene (Carey Mulligan), The Driver is the stereotypical cool male, too much so to share his true feelings with her, or really any vulnerability, as best revealed in one of the early scenes between them when she asks about his job as a stunt driver for the movies: “Isn’t that dangerous?” His response is to not respond, just offer a muted and telling smile that says “Of course it is, but a real man, a cool, composed man, would never admit it.” The real danger to The Driver is emotional honesty, and his sang-froid is the barrier between it and exposure. This is why he doesn’t speak to Irene in the elevator the first time we see them together, it’s why he avoids her and her son in the market, and it’s why he doesn’t interact with her until her car breaks down and his composure (not to mention his mechanical skillset) forces him to inject himself into her trying circumstance. It’s also why, later when their emotional bond has strengthened to the point that composure should fall away for the sake of emotional honesty, he again remains silent when she tells him her husband is coming home from prison. The Driver could state his case, he could offer himself, he could ask for her affections – which he knows she harbors – but his coolness, his composure, his sang-froid prevents him from revealing his true self, especially in the trying circumstance of her slipping through his fingers.

When it comes to this husband, Standard (Oliver Isaac), The Driver further subjugates his true will, in essence giving in to his composure, by not taking the dick-measuring bait Standard offers up in their first couple of meetings, and also by deciding to help Standard when he finds him pummeled by men who aim to have him rob a pawn shop to pay a protection debt. The Driver could have easily exposed Standard’s continuing criminal activities to Irene, or to the police, and removed the man, the hindrance, from the equation of he and Irene, but instead he puts himself in harm’s way because that’s what his composure would have him do: save the day – in this instance defined as sparing Irene from further hardships – by any means necessary. Crime is, after all, his business, and so far as The Driver is in charge, so long it’s his composure in control, business is good.

It’s in his business especially that The Driver is the epitome of composure. I mentioned his stoicism in the opening scene, and this is meant to establish his persona in all related matters. He has simple rules that he adheres to without pause or variation because they keep him safe, out of jail, and in high-standing with those in need of such services. His composure is his calling card, it is his résumé, and in a society that measures a man by his occupation, it is his worth, his value, his reason for being. But when in a diner he encounters an old client whose sense of discretion isn’t up to The Driver’s standards, his composure is exposed to a truly trying circumstance – one that could result in his outing as a criminal, with all the consequences personal and legal that implies – and so that composure falls away and we see him express violent tendencies for the first time when he tells the man: “How about this. Shut your mouth or I’ll kick your teeth in and shut it for you.” It’s at this point we learn his composure has a limit, and a graphically-brutal one, at that. We see now how composure when pressed becomes desperation, and desperation in some people, like The Driver, is a very, very dangerous thing. This scene starts the downhill slide into the bloody maelstrom of act three.

The Driver’s composure gets its greatest test to that point in the film in the form of the pawn shop robbery, and it doesn’t hold up, it doesn’t prevent the situation from going south, which it is supposed to do. Composure, after all, is only admirable if it works, it’s only a positive trait if it helps you keep your head level while everyone else is losing theirs. When Standard is killed and The Driver is left with money he now realizes they were set up to steal, there is no more need for composure, so he lets it go. He hits Blanche trying to find out the truth, and moments later when would-be assassins descend on the motel room, he kills them, their blood on his face at scene’s end a quite clear signifier that our story is about to enter its last and most-savage chapter. But before it does, Refn needs to show us that this violence isn’t reactionary or defensive; if it was, it wouldn’t be nearly as excessive – like his composure has been until now – as it’s going to be. So the director sends The Driver to a strip club to confront the thug who organized the robbery. Without even speaking a word The Driver smashes the thug’s hand and threatens to hammer a bullet into his skull if he doesn’t tell him who the money belongs to so The Driver can return it. As he crouches over the man with the hammer raised, ready to deliver on his threat, The Driver is trembling. The toothpick in his mouth is twitching up and down. This is a shaky mirror to the opening sequence, and proof that he has finally lost his grip on the sang-froid that defines him. He has given up on thought and given in to his inner sadism, and this isn’t a switch, a thing that can be flipped back and forth, it is a door that locks behind him. This is the scene in which The Driver opens the door. It is in the next that he closes it again, on the other, darker side now.

As I pinpoint it, the third act begins after the scene in the elevator in which The Driver kisses Irene then kills the hitman sharing their ride by stomping his head into jelly. Before this murder, The Driver finally and irrevocably revealed his emotions for Irene; after it, she reveals hers. The look on her face when the elevator closes between them at the end of this scene – an amalgam of shock, confusion, fear, disbelief, and disgust in this, in him, in herself, even – says it all in regards to this burgeoning relationship: it’s over, definitively, and it is never able to be repaired. Composure to The Driver was his way of interacting with the world, of being in the world, it was his way of keeping himself and his baser tendencies in check and thus safe. These tendencies, in fact, could have been the impetus for The Driver developing such composure. He could have come to a point in his emotional development where he realized he had to either learn to temper his violent side, or give in to it; wanting underneath it all to be if not good then “normal,” he would have tried to control himself, he would have believed his was an animal able to be tamed. He was wrong, but that doesn’t make his decision to try any less valiant; it does, however, make his failure that much more tragic.

From this moment until the end of the film The Driver’s composure, his sang-froid, is all but gone. Violence begets more violence, more violent violence, and culminates in The Driver’s own life seemingly up for forfeit. But it is then, in what are likely his last moments, in this most-trying of circumstances, that his composure returns. Instead of lying down to die or seeking help, instead of panicking or crying or lashing out in (more) pointless anger, The Driver re-seizes his cool. He gets in the last safe space he can think of, the last space reserved just for him – the driver’s seat – and he calmly, coolly, stoically sets off for the horizon. He will at least die composed, even if that same composure delivered him to death in the first place.

By titling Drive Sang-Froid in French, distributors let the audience in on a secret that American filmgoers had to discover for themselves: this isn’t an action film. Above all else and in its own brilliantly-bizarre fashion, Drive is a love story, it’s about the compromises to character that love can coerce, the thoughts and actions that go against our instincts but will not be ignored. Drawing attention to The Driver’s primary character trait, his excessively cool composure, before the film even starts turns it into the filter through which audiences view the film: if it’s there in the first act then like Chekov’s gun it must go off by the third. Now Drive – or rather Sang-Froid – becomes a waiting game, a fuse burning down to what one can only assume will be a spectacular explosion of composure, and a complete refusal of its more admirable aspects.

The Driver’s composure got him everything he had: his job(s), the people in his life, his safety, his freedom, his reputation. But it is the same composure that when pushed to excess by a series of trying circumstances, not the least of which is the irrevocable loss of the woman he loves, that drives him instead to the grave.

CinemaGrids: VERTIGO/TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN

It’s no secret that David Lynch holds Alfred Hitchcock’s VERTIGO as one of his favorite and most influential films.

MULHOLLAND DRIVE, for all intents and purposes, is a VERTIGO remake in which the woman dupes herself.

LOST HIGHWAY could be described the same way but with the woman in control, and intentionally cruel.

But perhaps nowhere is the pull of VERTIGO more evident in the canon of Lynch than in the two-part finale of TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN, which not only expands to the Nth degree upon the notions of duality VERTIGO toys with, but draws several visual parallels to Hitch’s masterpiece, as seen above.

CinemaGrids: HER/LOST IN TRANSLATION

Both Sofia Coppola’s LOST IN TRANSLATION and Spike Jonze’s HER are love stories unique to our modern, over-populated, connected-but-not-connecting society.

Both tell of emotionally isolated people scorned by love seeking to reestablish their hearts in hostile environments.

Both use the metropolis as a counterpoint and augmentation of their central characters’ loneliness.

Both star Scarlett Johansson.

Viewed from a certain perspective, the films can be seen as counterpoints, two sides of the same love story, or at least two chapters within it.

Coppola and Jonze were married from 1999 until 2003. LOST IN TRANSLATION was released in 2003. HER was released in 2013.

Essay: Lynch’s Lost Highway and the Paranoia of Intimacy

originally published 12/9/2016

David Lynch’s 1997 film Lost Highway was a bit of a comeback, as well as the start of a new chapter in his filmography, a chapter some – this author included – consider to be his best. Lynch’s previous feature had been Fire Walk With Me, the prequel film to his Twin Peaks series that was met with, shall we say, an unexpected response. Fans were hoping for a sequel, and when they realized what they were getting instead, they were not happy. The film was booed at its Cannes’ premiere – especially insulting considering Lynch’s film before that, Wild at Heart, had won the festival’s highest honor, the Palme D’Or – and is the worst-reviewed film of his career. At this particular point with the third season of Twin Peaks finally on the horizon, FWWM is starting to get a little more objective appreciation, but in its day it was regarded as a disaster, not just commercially – something Lynch has never cared about – but creatively as well, and in its aftermath Lynch entered a bit of a dry spell.

Of course, with an artist like Lynch there’s no such thing as a dry spell, the mere act of living is creative for him, but in terms of popular output, there was very little in the immediate wake of FWWM. He and Twin Peaks co-creator Mark Frost tried their hands at another TV show, On the Air, which came out a year after Twin Peaks ended and the same year FWWM was released, but of the seven episodes shot, only two aired before the series was cancelled. The next year, 1993, Lynch tried TV again with Hotel Room, a three-episode anthology of which he only directed two episodes. Then, for four years, nothing.

When Lynch did return to the world of feature filmmaking he did so with a vengeance, extrapolating off the themes of skewed identity and duality that Twin Peaks had raised, and reuniting with his Wild at Heart co-scripter Barry Gifford for the polarizing, visceral, and mind-bending but mostly-well-regarded Lost Highway.

Set in a city not unlike Los Angeles, Lost Highway is the parallel look at dueling identity crises, with a little fugue-state consciousness and intentional misdirection mixed in. The first part of the film deals with jazz saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette). Fred’s got it into his head that Renee is cheating on him, and Renee, with all her blasé nonchalance and skin-tight dresses, isn’t helping to dispel that notion. When strange, predatory videotapes start arriving on their doorstep, Fred’s paranoia kicks into high gear and he ends up apparently murdering Renee. I say “apparently” because Fred has no memory of the event, and only realizes what has happened once he plays another videotape, one that shows him next to Renee’s body, her blood on his hands. Midway through his incarceration, and the film, Fred inexplicably becomes Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a young man who’s been missing a few days and who has no recollection of where he’s been, what happened while he was gone, or how he ended up in a prison cell in place of a convicted murderer. Things get even further complicated – because somehow that’s possible – when Pete starts up an illicit relationship with a woman, Alice Wakefield (also Patricia Arquette), who’s either Renee by another name, or a dead ringer for her (a “doppelganger,” for Twin Peaks fans). Whoever she is though, she’s also the girlfriend of a vicious gangster (Robert Loggia) who won’t tolerate anyone making time with his woman.

Confused? You’re supposed to be. Lost Highway is a Möbius strip of narrative with no signposts along the way, it is a film seemingly built for multiple interpretations, and it signaled a new era in Lynch’s storytelling, one that was no longer concerned with plot as much as it was with themes. Though the themes Lost Highway tackles – misconceived, misrepresented, and misunderstood identity (self- and otherwise) – have been present in other Lynch films, most notably Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, what’s particularly interesting about Lost Highway is how the fractured identities of Lynch’s “protagonists” – Fred and Pete – are seemingly born of paranoia, and specifically of paranoia related to their closest, most-intimate relationships.

Anyone who’s ever been in a relationship can tell you there’s no one who has the capacity to hurt you more than someone you love. This is because you are your most vulnerable with them, and when instead of nurturing that vulnerability they take advantage of it, they use it to wound you, it has the most painful and life-altering consequences. And of all the ways love can wound you, infidelity is one of the worst. It is a refusal of your love, of you, and people are all-too-often physically hurt and even killed over such matters, it’s a story as old as the Ten Commandments and one you can find in pretty much any news feed any time of any day. Even the suspicion of infidelity can ruin lives. In Lost Highway, Lynch (and Gifford) examine this to an extreme degree, demonstrating not only how paranoia born of intimacy can lead a man to violent ends, but also how it can fundamentally – or in this case physically – turn him into someone else entirely. While their respective paranoias develop at different speeds and manifest in different, almost opposing ways, both Fred and Pete are unmade by their suspicions, not destroyed, necessarily, but definitely altered for the negative.

Because the characters of Fred and Pete are extensions of one another and thus share a fate, I’m going to focus solely on the impetus of all that happens in Lost Highway, the relationship between Fred and Renee. it is the paranoia inherent to their intimacy that sets in motion the many strange tragedies to come.

The paranoia that will be the undoing of nearly every character in the film is present from the opening scene. We see Fred first, answering the intercom and being told that “Dick Laurent is dead.” Fred doesn’t know a Dick Laurent, he can’t be sure the message is actually for him, and in fact he can’t even see the source of the message when he looks outside, but we can tell it raises a suspicion in him, one whose nature we learn about in the very next scene upon meeting Renee. The first time we see her she’s in a crimson silk dress that leaves very little to the imagination. This and her bright red lips scream sex. She’s the type of woman who attracts the attention of men and as her first words indicate – or perhaps Fred’s transferred paranoia would have us suspect – she just might be the type of woman who feeds off and even indulges that attention. The initial conversation between Fred and his wife has Renee opting out of watching him perform at a club that night. No sooner does she suggest she might stay home than Fred’s paranoia, perhaps on high-alert since the “Dick Laurent” message, manifests itself.

“What are you going to do?” he asks her.

“I thought I’d stay home and read,” she answers.

“Read? … Read what, Renee?”

By this brief exchange their relationship dynamic is established. He’s the needy one, she’s the independent one, he’s the paranoid one, she’s the one tired of bending to his paranoia. Her response to his question is to not respond. Instead she sits and sips a cocktail until he relents, sits next to her, and kisses her cheek. One giggle from Renee and the question of what she’ll be doing while he’s out is forgotten, or at least left unrepeated.

Later though, while at the club, Fred is compelled to call home. There’s no need, it’s only a few hours that he’ll be gone, but his paranoia won’t let him believe his wife. So he calls. And sure enough, there is no answer. Lynch walks his camera through their house as the phone rings but there’s no sign of Renee. Whether or not she’s there is neither confirmed nor denied, but the inference based on Fred finding her in bed when he gets home is that she slept through his call. However, we heard the phone and its shrill, clamorous ring, so we know no one could have slept through such a sound. Just as Fred’s paranoia flared when he hung up the phone, ours flares now. The difference is we are new to this relationship so still figuring out which of the participants to trust, still deciding which conclusions to draw. Fred has already drawn his and though he hasn’t completely articulated them yet, we can see how they make him feel by the grimace he wears: bitterly justified and angry, aggressively so. The harsh, blindingly-bright red light Lynch washes him in visually reinforces his percolating rage.

The next day the first tape arrives. Renee is the one who finds it, and as she’s opening the envelope in which it came, Fred sneaks up as though trying to catch her in some secret; the way she startles suggests she might have one or two. He asks her who the tape is from, not absently wondering aloud but directly pressing her, like he expects her to have the answer. She doesn’t. He has to coax her to sit down and watch it with him – “Come on” – and when she acquiesces there is a notable space between them on the couch, almost like she’s preparing herself for a quick escape. The tape shows nothing but the exterior of their house, causing Renee to speculate it must be from a real estate agent. The dubious air surrounding them would have us wonder if she believes this, or if she’s just dispelling his suspicion. In the very next scene, Fred is remembering/imagining her leaving the club with another man, and when these images dissipate he is in bed and she is standing next to it, disrobing to nude. This juxtaposition of image and reality lets us know where Fred’s thoughts about Renee and the other man were headed – towards infidelity – and when moments later they begin making love, it is an obvious sexual reclaiming of Renee by Fred, while at the same time also a refusal of his paranoia, an act to convince himself she still loves him. He finishes and rolls off her seemingly confused and distressed while she’s stone-faced and emotionless, like this was a joyless exercise for her, some dreaded duty. He tells her a dream he had in which she was in bed – a lover’s locale – but it wasn’t really her. This is him admitting, in a roundabout way, that he isn’t sure Renee is who she seems to be, a faithful wife and committed partner. Then, in reality, he sees the face of a strange, ghastly, and mysterious man (Robert Blake) over hers, a sign his paranoia is crossing over from fantasy into a fantastic reality.

When the second tape arrives, again Renee is the one to discover it and again Fred startles her. She tries to ignore the tape, but he won’t let her.

“Don’t you want to watch it?”

“I guess so.”

He’s practically daring her, and she’s passively evading. Twice he has to ask her to watch, and when she yields the distance between them on the couch is again noticeably vast. On the tape, the camera moves from outside to inside and becomes terrifyingly more intimate. They call the police but when detectives arrive, Fred withdraws, becomes defensive, fueled by surging paranoia. This invader, he seems to be wondering, could it be Renee’s lover? She is calm with the police, helpful, even, in her placid, seemingly unconcerned way.

Next we see the couple they are at a party and hanging out with the same man, Andy (Michael Massee), who Fred saw in his memory/imagination with Renee. Andy and Renee are friendly, handsy, and towards Fred Andy is mockingly dismissive, all of which teams with the videos to play into Fred’s mounting paranoid suspicions. Then the Mystery Man from Fred’s vision shows up.

Mystery Man says they’ve met before, at Fred’s house, though Fred has no recollection of this. Mystery Man says he’s there right now and calls Fred’s house to prove it. Sure enough, someone with a voice identical to Mystery Man’s picks up the phone. If Fred’s paranoia was played with before, it is manhandled now, specifically his paranoia that another man has been in his house, and by extension his bed, a man there to replace him in his marriage, a man there to ruin him, possibly even to kill him.

This one, absurd, and horrifying encounter is all Fred needs to submit to his paranoia, to convince himself it isn’t paranoia at all, but an accurate perception of his marriage. This, in turn, allows him to act on his paranoia as well. Renee approaches him. He blows her off to ask Andy about Mystery Man. Andy says the man is a friend of Dick Laurent’s, the name of the dead man spoken at the film’s start. Fred grabs Renee and they leave.

On the drive home, Fred’s paranoia is given voice.

“How’d you meet that asshole, Andy, anyway?”

“…He told me about a job…”

“What kind of job?”

“I don’t remember…anyway, Andy’s okay.”

“Yeah, well, he’s got some pretty fucked up friends.”

Fred is testing her in this exchange, not just her truth-telling ability which is shaky at best but also by passing judgment on Andy, seeing if she will agree with her husband or defend the other man. Her silence we – and Fred – take as defense.

When they arrive home Fred goes inside himself. Finding nothing there, he returns to her on the stoop and admits this part of his paranoia to her:

“I thought there might be somebody inside.”

What he doesn’t admit was that he thought perhaps the someone inside was related to her infidelity, which he no longer suspects, he believes. His leaving her in the car while he searched the house wasn’t an act of protection, then, it was a hunt, he was looking to arm himself with facts before facing her again. But in the face of no facts, only confounding circumstances, Fred is left percolating in his paranoia with nowhere to pour it, meaning it’s just going to build and build and build.

Later, Fred leaves the bedroom for the darkness of the house and returns only when Renee steps to the edge of that darkness and calls him back. But it is not Fred who returns, not mentally. His paranoia is no longer suppressed, it is in charge. The darkness follows him into the bedroom until it takes over the entire screen.

The next morning Fred finds a third videotape. He watches it alone, no longer trusting Renee, subconsciously perhaps knowing it’s not even an option because she’s dead. The tape proves it, as it would seem to prove he’s her killer, shown as he is next to her badly-mutilated body in a frenzied state, his hands, arms, and torso slick with her blood. He can’t remember the crime, he doesn’t want to believe he did it, but he can’t convince himself it isn’t true, as now his paranoia, with nowhere else to go, is extended to himself and his capabilities.

Everything that happens from here – Fred’s incarceration, his molting into Pete, Pete’s love affair with Renee’s doppelganger Alice, Mr. Eddie/Dick Laurent’s realization of their affair, the resulting threat on Pete’s life that leads to the robbery in which Andy is killed, the flight of Pete and Alice that ends in the desert with some lovemaking, some betrayal, and some molting back into Fred, then the kidnapping and execution of Dick Laurent, and lastly Fred returning home to speak into the intercom the very words that opened this mystery, “Dick Laurent is dead” – all stems from Fred’s initial break from reality, mentally and physically, which is caused directly by the paranoia sparked in him by his most intimate relationship, that with his wife. The character of Pete has his own issues with paranoia, some directed at himself and the time he was missing that he can’t remember, some directed towards his illicit relationship with Alice and the threat it provokes, but these are extensions, or perhaps echoes of Fred’s paranoia. It is Fred, after all, that the film starts and ends with. In the first act, Fred is consumed by his paranoia; in the third, he purges himself of it. Already he has eliminated Renee, and once the Dick Laurent prophesy has been fulfilled, Fred’s paranoia is gone, but so is his life. This is why he doesn’t deliver the message in person, there’s nothing left of him in that house, not even in the him still residing there.

Lost Highway is a film about many things, but mostly it is about identity: how we see ourselves and how we project ourselves to others, the latter born of fear, or paranoia, that the real us won’t be enough. As it is presumed that the person with whom you choose to make your life, and who in turn chooses to make their life with you, is the one who loves that real you the most, it is especially insidious that marriage is the Eden into which the director released his paranoid serpent. And just like in that famous instance, the result here is banishment, Fred’s from his marriage, his old life, his old self, even, and on a very real level, from the notion of reality as he understood it. That Lost Highway of the title, that’s the one Fred’s taking out of everything he’s ever known, and the only place it leads is right back to the beginning so his paranoia and the horror it wreaks can start all over again.

In some cultures they call that Hell. In Hollywood they call it Lynchian.